|

|

A fictional talk, to get started by Silvia Nanclares.

This text is part of the material which we were working on first residency at Seville.

me/here

I’m Silvia Nanclares, and I write stories. Some stories, some blog posts, some scriptwriting, some articles. I always do it from an autobiographical, self-fictional point of view. Writing is almost the thing I most like doing in this world. I also coordinate Creative Writing groups, so I have spent some time studying the guts of stories in order to find some good ways of telling them (this varies, and depends on each story, but there are some general patterns: basic tools). People often ask me whether it is possible to teach writing, and I answer that I don’t know, but that my experience tells me that these tools, once detected and set in play, can improve a lot how your stories reach people. The skill to touch and awaken the interest of the other is something that requires a technique, indeed. This is the technique of narration. And this is what I expect, with the help of Nuria (Nuria G. Atienza, documentary film maker and coordinator of the education through audio-visual production workshops. Co-coordinator of the Narratives module within the European Souvenirs) and the team, to transmit to you: a few tools that can make what you want to tell reach your audience more efficiently.

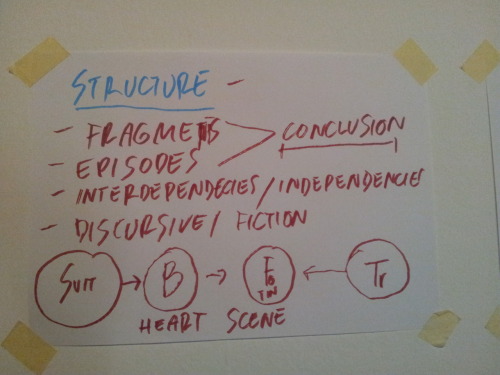

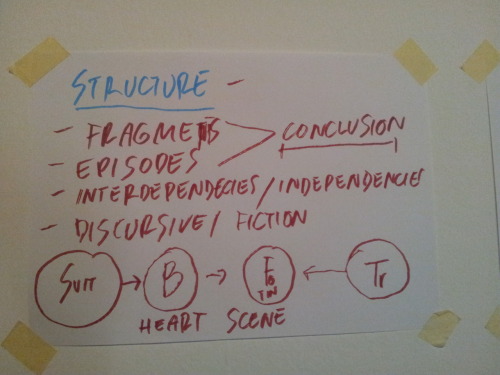

Structure – Seville Residency. (cc) ZEMOS98 memory/archive

In auto-biographical writing, I use my memory as an archive on which to deploy the technique of fiction. This is how I document my life, so that it can stop being only mine. So that it can become anyone else’s. I use fiction in order to build a truth. Lacan said: Truth has the structure of fiction. Structure is one of the tools, if not the most important tool, that we will deal with these days. Truth has nothing to do with reality. Truth is built (and politicians know a lot about this) with techniques of fiction. Imagination as a political muscle at the service of the most disparate ideologies. But the collision between stories can also be put at the service of the liberation of ideas.

technique/fiction

After being put through the machinery of fiction, my memories (my life souvenirs) become literary motifs, re-combinable pieces at the service of the story I want to tell. Things apparently unordered and bereft of meaning are thus joined together in order to build fiction. My work is precise: it consists in creating a form (language, style, structure) premised on my memories, that can allow me to narrate ideas which can concern and touch other people. On the basis of something as apparently private and intimate as a memory, I try to cross the bridge over to the common, towards a possible identification.

aesthetics/content

To procure an aesthetic which can be at the service of, or contained within, an ethics. Form at the service of content. The mode in which I say things at the service of what I want to narrate. Technique at the service of narration. Narration at the service of the idea. When we deal with structure, we’ll see that ideas can also be protagonists in stories, and can have conflicts with each other that can configure a plot.

us/here

We are here to do something similar. To select re-combinable pieces from our personal archives (in this case, “national” archives, representatives of a “collective personality”, of a shared and common intimacy) that can allow us to build a common narrative which can appeal to anyone.

broadcast europe

I was brought up in a middle class area of the city of Madrid. My family is typical of Spain in the seventies, of Spain after the dictatorship. Three children, Mom worked as a housewife, and Dad left home in the morning to go to work, and would come back at night. My father ran a company that represented broadcast firms (it took me decades to understand this word), and used to travel a lot. He would travel abroad, look for equipment (cameras, editing tables and other products) in order to distribute them here, in order to provide a country (Spain), whose telecommunications system was booming during the 80′s and 90′s. My father defines himself as a technocrat. “I’m a man with no imagination”, he usually adds.

fetish objects

I’ve got a fetish object at home, which I could consider a family souvenir, from my father: this object here. This little notepad, where he would write down all the flights he took during over 40 years of professional career. A register. An archive of flights. This is my father, a very important part of him. He travelled a lot through Central Europe, the so- called Western Europe. Also to Japan and the USA, but above all Europe. He made us admire that Europe, his Europe: Germany, Holland, the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Italy. That idea of Europe is what I was brought up on at home. A buoyant, strong, technified and wealthy Europe. He would travel almost every month, and always brought back a present to each of us from the cities he had visited. That moment was a ritual in itself. The moment that Dad would put his suitcase on the table and rummage through the clothes in search of the bags with our presents. I especially remember his arrival from a long stay in Japan: kimonos for Mom, a bottle of sake, a Rubik cube, a Nintendo, some prints of geishas. Our house started filling up with souvenirs: German beer mugs, London double-decker bus magnets, Norwegian salmon, Swiss chocolate, t-shirts with typical national slogans.

stories

But there were also immaterial memories, his stories. Like that time that a man tried to seduce him on a train from Rome to Pisa (that was when there were ABSOLUTELY NO homosexuals in Spain), or that story of the only other Spanish speaker he ran into in Japan being a Chilean Pinochet-supporter, whom he couldn’t talk about anything at all without having a row. He would also bring us information and impressions from Europe, such as trains being on time, that at four o’clock in the afternoon it was already night-time, or about how people respected the queue at cash machines. The recreations of these stories and memories are what informed my first idea of Europe.

“in europe”

I once had a boyfriend who told me that on January 1st 1986 his mother woke him and his brothers up really early, dressed them up really well, prepared them excellent breakfast and sat the whole family in front of the TV to watch the ceremony of Spain’s entrance into the EEC (currently, the EU). Not long ago, I spent some time in France, and people would be very surprised to hear me use the expression “in Europe”. The fact is, I didn’t grow up feeling part of Europe, maybe that was because of political circumstances, and to that halo of otherness and idealization that my father’s stories, souvenirs and travels transmitted to me. For better and for worse, sometimes fiction can have this distancing effect.

1992

That year, I was seventeen, and had already started questioning the official family story. Barcelona hosted the first Olympic Games to take place in Spain, Seville was host to the Universal Expo, and Madrid was European Cultural Capital. It was time to introduce ourselves to the world. And to obtain all kinds of infrastructure; in a nutshell, to become European. For this purpose, we had a budget, called the European Social Budget. We have grown thanks to this budget. Which, by the way, is already spent. It’s like when your parents stop your allowance. In 1992, Europe and the world came to visit us, and we brought out the heavy artillery of stereotypes. We turned our souvenirs into a fashion: happiness, sunshine, the Mediterranean, colour, heat. It was madness. I remember the wooden Japanese Pavillion at the Expo; the heat would make the wood swell, and it had to be repaired halfway through the exhibition. Pavillion. This notion of a Universal Expo is totally pre-Internet, isn’t it? So is the idea of bringing or taking a souvenir from another country. Nowadays anything, except the immaterial, can be purchased anywhere. And what isn’t, is on youtube.

secrets

I’m under the impression that life beings in 1975, the year I was born. This is partly due to the fact that I was born on the final year of Franco’s dictatorship. The desire to forget is very strong. At home, my parents rarely spoke of their childhood and adolescence, as if by not mentioning the Post-War period, when cold temperatures and deprivations were a matter of everyday life, History would become blurred until vanishing. Who wanted to talk of other times, now that we had central heating, supermarkets filled up to the tip, and television with an MTV channel? But there were the pictures. One night, at my grandmother’s place (and this is a secret I’m first revealing here), while she was sleeping, I picked out and stole a whole bunch of pictures from her personal archive, called “the tin with the photos”. There were some pictures from their brief exile to France: the only “Europe” that my grandparents ever set foot on, and a family taboo. I felt that I had suddenly recovered a whole story which my parents’ silence had refused. The worst thing wasn’t me stealing these pictures, the worst thing was that, a few years later, after moving house a few times, I lost them. I have lost a part of my family’s memory. I’ve created a void on the basis of another void.

redefinition/fiction/remix/rendition

In order to fill this void, right now I’m writing a novel entitled broadcast, where I’m trying to redeem myself through fiction. In the novel, I’m trying to reconstruct, one by one, the stolen pictures I can remember, and to create a story with them. Like scenes, the pictures would lead into one another, until forming a new family history. False memories Truer than official history. That’s what I have, that’s what I know how to do: to fictionalise on the basis of memories. In order to attempt to rescue that which is irretrievably lost. From the private to the universal, passing through fiction. The autobiographical remix as a technique to re- write History, in this case, family history. This is how archive-based narrative works, like an imaginary broadcast, maybe closer to the truth than any documentary that pretends to be objective.

snippets/coast

with the snippets of Europe that kept arriving at my flat in Madrid I built my self an idea of Europe which was very much premised on progress in the telecommunications sector, with technological infrastructure as a safety measure, the Europe of the common market; a very Duty Free-like poetic. Also, a Europe with social rights. In 2007, I accompanied my father to IBC, in Amsterdam, one of the largest fairs in this sector. These are the pictures I took in Amsterdam (see Flickr set), what I found interesting there. The Jordaan quarter. A pink intercom. The terrace of a bar. An antique market. One of the few times I could stroll around the fair, my father looked at my with an expression of fascination, and told me he wanted to show me something. He took me to the back of the buildings, walked past a few giant broadcasting trucks, and showed me this (photo of connected cables). A mesh of cables that made life and communication possible for the stands indoors. That was what my father found fascinating. Communications. Cables. Connections. Machines. Perplexed, and with a dose of irony, I took note of the narrative and vital abyss that separated us. But I also felt the many bridges that united us, especially those of affection. Whether we like it or not, we are attached to many stories that don’t quite represent us, but that have made us who we are.

memory/identity/voice

What we choose to remember, to register, that which fascinates or repels us, determines our memory and the identity that we assign to things and to places. Mi current narrative on Europe (based on my own memories and ideas) has been inexorably affected by this paternal image of fascination with the cables, and we could almost say that it was forged in opposition to it. The childhood/juvenile/family narrative of the progressive, merchant, technological Europe was my point of departure from where to locate myself in the “global world”. My notion of Europe owes a lot to the narrative of Europe of my father: patriarchal, productivist, and social-democrat. And this is neither good or bad, it’s a fact that must be recognised. It is crucial to be aware of what memory we are starting off from, and what other kinds of memory or struggles of memories we want to voice with our stories. The selection we will make from our own archive, the voices and versions of the stories we would like to host in our collective narrative will constitute, by themselves, a fairly politically-charged gesture. The contents and final aesthetic of the memory we build will speak for us.

some code, please

with this fictional-talk, I have attempted to appropriate the issues posed by the European Souvenirs project: how can memory and official narratives condition identity and how it is important to give a voice to other, non-subsidiary representative memories. I have problematised the idea, by running it through my own experience, and creating a certain fictional texxture, since that is my knowledge methodology. In order to share it, I have put on the table and revealed my life experience, my memories, my souvenirs and the ideas that have been prompted by them, with the aim of creating a story.

I invite you to appropriate some of the issues launched by this project: choose subject matter you’re interested in, that transverses you or that appeals to you individually or as a group, from your individual, everyday point of view, in order to later be able to pay full attention at building the bridges that will weave a common code and will build a collective story with the capacity to emotionally and intellectually touch any spectator. each story develops its own code. and that code is only revealed while the story is being told. it’s not something you can do a priori. so, let’s get started…

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

|